July 31, 2025|ו' אב ה' אלפים תשפ"ה Matos/Masei 5785 - Travelling Back Towards Ourselves

Print ArticleShai Agnon was an Israeli novelist, poet, and short-story writer, and really one of the central figures of modern Hebrew literature. In 1966, he received the Nobel Prize for Literature.

At that time, he was asked about his birthplace. To the interviewer's surprise, Agnon answered that he was born in Jerusalem. The interviewer pointed out that everyone knew he was born in a small town in Galicia, not in Jerusalem.

Agnon corrected him, "I was born in Jerusalem more than three thousand years ago. That was my beginning. That was my origin. Galicia is only one of the stopping off points along my way back home."

The final parsha in Sefer Bamidbar, Parshas Masei, describes the journey and the stops along the way that Am Yisrael took as they travelled from Egypt to Eretz Yisrael.

And as the Torah introduces these different stops along the journey, it tells us the following:

וַיִּכְתֹּב מֹשֶׁה אֶת מוֹצָאֵיהֶם לְמַסְעֵיהֶם עַל פִּי יְקֹוָק וְאֵלֶּה מַסְעֵיהֶם לְמוֹצָאֵיהֶם: (פּרק לג פּסוק ב)

It's a difficult pasuk even to translate. But I'll try:

And Moshe wrote down their starting points or origins to their journeys or destinations, all done according to Hashem's command. And these were their journeys or destinations according to their starting points.

And even as it's hard to translate that first phrase, מוֹצָאֵיהֶם לְמַסְעֵיהֶם, the starting points to their journeys. The Torah then inverts the phrase and repeats it: וְאֵלֶּה מַסְעֵיהֶם לְמוֹצָאֵיהֶם.

And this raises -- at least -- two questions:

1) Why the repetition?

2) What does the second part of the pasuk even mean? Why would someone go from their destination back to the starting point? And why would it be important for the Torah to talk about it?

The Baal HaTurim writes that it is written backwards and forwards to emphasize that every stop along the way, every decision about where to go, was determined by Hashem. In fact, there were times when Hashem even had the people go back the way they had come, which must have challenged their Emunah. So comes the pasuk and writes the phrases in both directions, forward and backward, to emphasize that every stop was part of Hashem's plan.

Rashi quotes a mashal, a parable, from Rabbi Tanchuma. He says: imagine there was a King whose child was sick, and he took the child on a long journey to the doctor and back home. And afterwards, once they are home, they review the trip: Remember when we stopped at that hotel! Remember how hard it was to get through the third night when you weren't feeling well! Remember when we got lost and we had to go back around the other way! Showing the child how there was value not only in the fact that eventually he got better, but that the journey itself had so much value for their relationship!

Both of these ideas reflect the Torah's perspective that the game of life is not about reaching some far-off destination. The value is found in each step of the journey itself.

But I want share with you a third explanation as well.

Rabbi Shlomo Riskin asks the same question: Why the contradiction in the pasuk, but maybe most concerning, why the emphasis on travelling from your destination (Maseihem) back to the origin (Motza'eihem)?

And he answers that the Torah telling us about a journey from our destination back to where we started is not only not troubling, it is part and parcel of what it means to be a Jew! Because Jews have always traveled backwards!

He writes:

"Fundamental to our history as a nation is that we are constantly traveling -- in all of our wanderings, on the road to the Promised Land...Our traveling is not an aimless wandering; it is with a clear compass and a purposeful direction...backwards... As we Jews have moved down the road of time, we have and will always continue to keep in front of our eyes, the place of our origin....to return to the place where we began."

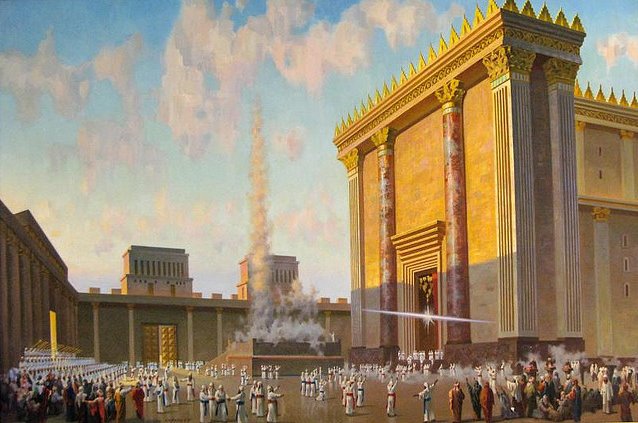

Immediately after the destruction of the Beis HaMikdash, Chazal instituted a halacha that whenever a person davens, we face Eretz Yisrael. Every Shmone Esrei that we would daven after leaving Eretz Yisrael would contain multiple brachos and other references to our desire not to move forward after galus, but to get back to Eretz Yisrael, to Yerushalayim.

Rabbi Riskin also notes that it is because we know where we are headed, because of the singular focus Am Yisrael has about our eventual return back home to Eretz Yisrael, that we have had the strength and fortitude to make it through each of the Masa'ot, each of our stops along the way in galus.

A story is told about Napoleon. As he was making his way through Europe, he passed a shul and heard crying inside. He decided to go inside, and he saw a group of Jews sitting on the floor in tears. He asked them "why are you crying?!" They said, "Because of our temple which was destroyed on this day". It was Tisha B'Av. Napoleon responded, "how long ago was your temple destroyed?" They responded, "About 1,700 years ago". Napoleon then exclaimed out loud "A People that mourns its temple 1,700 years after its destruction will surely live to see its rebuilding".

Former Chief Rabbi Yisroel Meir Lau writes in his autobiography about the emotional and frightening moment when the Nazis separated him from his only remaining family member, his brother Naphtali, who had taken care of him throughout his time in the concentration camps. Rabbi Lau was a young boy of only 8 years old when his older brother, unsure if they would ever see each other again, presented him with some final instructions:

"I've come to tell you that there is a place in the world called Eretz Yisrael. Say it with me, "Eretz Yisrael", the land of Israel. Again. Repeat it with me."

Rabbi Lau records at that he knew not one word of Hebrew, but he repeated those two words, Eretz Yisrael, over and over again, without having any understanding of their meaning.

His brother concluded, "If you stay alive, you will surely meet people who will want to take you with them to other places because you're a nice kid. But you aren't going anywhere else. Remember what I say, only Eretz Yisrael. Remember, Eretz Yisrael." And with that Naphtali Lau walked away and disappeared into the distance.

The Nine Days are a difficult time. In fact, Rav Chaim Friedlander writes that if a person feels uncomfortable, if they don't like the Nine Days, that's also something to be proud of. It means these days move you at least a little bit.

But in reality, the Nine Days are an opportunity. An opportunity to take a look backward at our connection to our essence, to who we are as a people connected to our land. Because if we know where we come from and we know where we are going, then we can figure out what we need to do to get there.